All decisions are wrong, but some are better

Everything is fucked, no systems are sound, all decisions are wrong, and we should destroy all software.

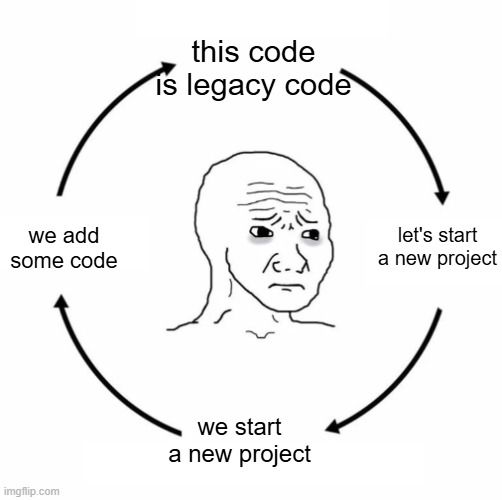

I've noticed this recurring trend at my last several companies:

- We have an existing project. People take jabs at it, commenting on how it's "a mess" and "legacy code". I've seen this applied to decades-old systems as well as three-year-old ones.

- We start a new project. People are happy, commenting about how it's nice to get a fresh start, stick to "clean code", and avoid making the mistakes made on the other project.

These are perfectly reasonable attitudes. Software systems grow in complexity, and some can turn into messes really quickly. Working on a greenfield project is always great—who doesn't like a fresh start? A decade ago, I was the one advocating for and proposing software rewrites. Let's clean up the mess!

But there's a last part of the loop:

- Eventually, people start realizing: We may not make the mistakes of the other project, but we'll make our own set of mistakes. Our code ends up being legacy code.

But here's the thing: it's the circle of life!

There are no perfect systems. Our code evolves, has to handle more cases, becomes legacy. It becomes full of cruft, tradeoffs and pain. How do we avoid this?

First, know that these two things are true:

- All decisions are wrong. All architectures are inadequate. All abstractions are poor. All nontrivial code is hard to read.

- Some decisions are less wrong than others. Some architectures are better than others. Some abstractions are better. Some code is easier to read than others. Some systems are easier to work with.

However, the line between "wrong" and "less wrong" is more than just your feeling of legacy and confusion. Unless you start a new project every three years, you'll still end up with that feeling. There must be a better way.

All decisions are wrong

You'll never architect the perfect system. Oh, using integers for IDs is bad because of enumeration and overflow? How about UUIDs? Oh, that's bad for storage and search performance? How about some other random ID format? And so on, and so forth. There will always be some bottleneck, some situation that you can't fix.

During design/architecture discussions, I tell folks, "We need to accept that whatever decision we take is the wrong one. We just need to pick one we can live with." Once you go beyond CRUD, you begin to solve problems where you have to play by certain constraints. Because of this, you can't merely pick an idealized solution.

But some are better

That said, it is undeniable: there are clearly some ways that are worse. Fetching all items from a database and letting the client paginate it is obviously a worse decision than implementing pagination on the backend. But in real-world business cases, we deal with a lot more non-obvious situations. Should we normalize or inline this data? Should we use strings or integers here?

My litmus test is this: If you claim that a certain architecture/design is worse than another, you must be able to:

- point out its problems (with data, preferably)

- point out its strengths (Yes, you need to try to understand why it was chosen in the first place.)

- explain why the alternative fits this situation better

- point out the problems of the alternative

In summary, it is not enough to say "This code sucks." You must be able to say why it sucks, why it might have been chosen, point out a better option, and acknowledge the tradeoffs involved.

It's not just about what you do, it's about how you do it

In the best systems I've worked on, there were some unconventional things that had to be done. These were things that might make a new joiner immediately go "WTF". And yet they did not make the system a pain to work with. How?

-

First, picking and sticking with conventions.

I used to be very anti-convention, feeling that they stifled creative freedom and experimentation. That can be true. But I've also come to see that going with a convention, even a poor one, makes things easier for everyone. We don't have to judge these situations afresh every time, deciding again on each one. We can save our energy for the important decisions.

-

Next, documenting assumptions, decisions and details. Make things easy to find.

Document the conventions. Document when and why you stray from these conventions. One of the biggest things that makes a codebase "age" quickly is developers doing strange things and leaving no explanation. Write, write, write. Write comments, write pull request descriptions, write wiki docs, draw diagrams. Leave breadcrumbs. Even if the system is a mess, make it an understandable mess. Better overdocumented than undocumented.

-

Finally, an attitude of constant improvement. The best systems I worked with recognized that the system was a living, evolving being. Rather than fixating on "getting it right" from the start, we were open to suggestions for improvements. We encouraged people to fix things they saw wrong, or propose new conventions if they solved problems we were having. Sometimes, we had a running list of technical improvements we wanted to work on, and encouraged folks to pick up tasks from there.

The human cost

We struggle with these legacy systems, not merely because they're technically worse, but because they overload us. They either require more developers, or they place a larger mental burden on each developer. They require more intricate solutions to common problems, or more effort to change or adjust things. One of my worst experiences was a project where changing a simple label in the UI took me three days. It really sucked, and had me questioning my skills.

So whether architecting our new system, or living with the old, an important question to ask is How can I reduce the human cost here? How can I make things easy to discover? How can I make the system easy to change?

I write about my software engineering thoughts and experiments. Want to follow me? I don't have a newsletter; instead, I built Tentacle: tntcl.app/blog.shalvah.me.