How to build a math expression tokenizer using JavaScript (or any other language)

Some time ago, I got inspired to build an app for solving specific kinds of math problems. I discovered I had to parse the expression into an abstract syntax tree, so I decided to build a prototype in Javascript. While working on the parser, I realized the tokenizer had to be built first. I’ll walk you through how to do one yourself. (Warning: its easier than it looks at first.)

What is a Tokenizer?

A tokenizer is a program that breaks up an expression into units called tokens. For instance, if we have an expression like “I’m a big fat developer”, we could tokenize it in different ways, such as:

Using words as tokens,

0 => I’m

1 => a

2 => big

3 => fat

4 => developer

Using non-whitespace characters as tokens,

0 => I

1 => ‘

2 => m

3 => a

4 => b

…

16 => p

17 => e

18 => r

We could also consider all characters as tokens, to get

0 => I

1 => ‘

2 => m

3 => (space)

4 => a

5 => (space)

6 => b

…

20 => p

21 => e

22 => r

You get the idea, right?

Tokenizers (also called lexers) are used in the development of compilers for programming languages. They help the compiler make structural sense out of what you are trying to say. In this case, though, we’re building one for math expressions.

Tokens

A valid math expression consists of mathematically valid tokens, which for the purposes of this project could be Literals, Variables, Operators, Functions or Function Argument Separators.

A few notes on the above:

- A Literal is a fancy name for a number (in this case). We’ll allow numbers in whole or decimal form only.

- A Variable is the kind you’re used to in math: a,b,c,x,y,z. For this project, all variables are restricted to one-letter names (so nothing like var1 or price). This is so we can tokenize an expression like ma as the product of the variables m and a, and not one single variable ma.

- Operators act on Literals and Variables and the results of functions. We’ll permit operators +, -, *, /, and ^.

- Functions are “more advanced” operations. They include things like sin(), cos(), tan(), min(), max() etc

- A Function Argument Separator is just a fancy name for a comma, used in a context like this: max(4, 5) (the maximum one of the two values). We call it a Function Argument Separator because it, well, separates function arguments (for functions that take two or more arguments, such as max and min).

We’ll also add two tokens that aren’t usually considered tokens, but will help us with clarity: Left and Right Parentheses. You know what those are.

A Few Considerations

Implicit Multiplication

Implicit multiplication simply means allowing the user to write “shorthand” multiplications, such as 5x, instead of 5*x. Taking it a step further, it also allows doing that with functions (5sin(x) = 5*sin(x)).

Even further, it allows for 5(x) and 5(sin(x)). We have the option of allowing it or not. Tradeoffs? Not allowing it would actually make tokenizing easier and would allow for multi-letter variable names (names likeprice). Allowing it makes the platform more intuitive to the user, and well, provides an added challenge to overcome. I chose to allow it.

Syntax

While we aren’t creating a programming language, we need to have some rules about what makes a valid expression, so users know what to enter and we know what to plan for. In precise terms, math tokens must be combined according to these syntax rules for the expression to be valid. Here are my rules:

- Tokens can be separated by 0 or more whitespace characters

2+3, 2 +3, 2 + 3, 2 + 3 are all OK

5 x - 22, 5x-22, 5x- 22 are all OK

In other words, spacing doesn’t matter (except within a multi-character token like the Literal 22).

-

Function arguments have to be in parentheses (sin(y), cos(45), not sin y, cos 45). (Why? We’ll be removing all spaces from the string, so we want to know where a function starts and ends without having to do some “gymnastics”.)

-

Implicit multiplication is allowed only between Literals and Variables, or Literals and Functions, in that order (that is, Literals always come first), and can be with or without parentheses. This means:

- a(4) will be treated as a function call rather than a*4

- a4 is not allowed

- 4a and 4(a) are OK

Now, let’s get to work.

Data Modelling

It helps to have a sample expression in your head to test this on. We’ll start with something basic: 2y + 1

What we expect is an array that lists the different tokens in the expression, along with their types and values. So for this case, we expect:

0 => Literal (2)

1 => Variable (y)

2 => Operator (+)

3 => Literal (1)

First, we’ll define a Token class to make things easier:

function Token(type, value) {

this.type = type;

this.value = value

}

Algorithm

Next, let’s build the skeleton of our tokenizer function.

Our tokenizer will go through each character of the str array and build tokens based on the value it finds.

[Note that we’re assuming the user gives us a valid expression, so we’ll skip any form of validation throughout this project.]

function tokenize(str) {

var result=[]; //array of tokens

// remove spaces; remember they don't matter?

str.replace(/\s+/g, "");

// convert to array of characters

str=str.split("");

str.forEach(function (char, idx) {

if(isDigit(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Literal", char));

} else if (isLetter(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Variable", char));

} else if (isOperator(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Operator", char));

} else if (isLeftParenthesis(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Left Parenthesis", char));

} else if (isRightParenthesis(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Right Parenthesis", char));

} else if (isComma(char)) {

result.push(new Token("Function Argument Separator", char));

}

});

return result;

}

The code above is fairly basic. For reference, the helpers isDigit() , isLetter(), isOperator(), isLeftParenthesis(), and isRightParenthesis()are defined as follows (don’t be scared by the symbols — it’s called regex, and it’s really awesome):

function isComma(ch) {

return (ch === ",");

}

function isDigit(ch) {

return /\d/.test(ch);

}

function isLetter(ch) {

return /[a-z]/i.test(ch);

}

function isOperator(ch) {

return /\+|-|\*|\/|\^/.test(ch);

}

function isLeftParenthesis(ch) {

return (ch === "(");

}

function isRightParenthesis(ch) {

return (ch == ")");

}

[Note that there are no isFunction(), isLiteral() or isVariable() functions, because we testing characters individually.]

So now our parser actually works. Try it out on these expressions: 2 + 3, 4a + 1, 5x+ (2y), 11 + sin(20.4).

All good?

Not quite.

You’ll observe that for the last expression, 11 is reported as two Literal tokens instead of one. Also sin gets reported as three tokens instead of one. Why is this?

Let’s pause for a moment and think about this. We tokenized the array character by character, but actually, some of our tokens can contain multiple characters. For example, Literals can be 5, 7.9, .5. Functions can be sin, cos etc. Variables are only single-characters, but can occur together in implicit multiplication. How do we solve this?

Buffers

We can fix this by implementing a buffer. Two, actually. We’ll use one buffer to hold Literal characters (numbers and decimal point), and one for letters (which covers both variables and functions).

How do the buffers work? When the tokenizer encounters a number/decimal point or letter, it pushes it into the appropriate buffer, and keeps doing so until it enters a different kind of operator. Its actions will vary based on the operator.

For instance, in the expression 456.7xy + 6sin(7.04x) — min(a, 7), it should go along these lines:

read 4 => numberBuffer

read 5 => numberBuffer

read 6 => numberBuffer

read . => numberBuffer

read 7 => numberBuffer

x is a letter, so put all the contents of numberbuffer together as a Literal 456.7 => result

read x => letterBuffer

read y => letterBuffer

+ is an Operator, so remove all the contents of letterbuffer separately as Variables x => result, y => result

+ => result

read 6 => numberBuffer

s is a letter, so put all the contents of numberbuffer together as a Literal 6 => result

read s => letterBuffer

read i => letterBuffer

read n => letterBuffer

( is a Left Parenthesis, so put all the contents of letterbuffer together as a function sin => result

read 7 => numberBuffer

read . => numberBuffer

read 0 => numberBuffer

read 4 => numberBuffer

x is a letter, so put all the contents of numberbuffer together as a Literal 7.04 => result

read x => letterBuffer

) is a Right Parenthesis, so remove all the contents of letterbuffer separately as Variables x => result

- is an Operator, but both buffers are empty, so there's nothing to remove

read m => letterBuffer

read i => letterBuffer

read n => letterBuffer

( is a Left Parenthesis, so put all the contents of letterbuffer together as a function min => result

read a=> letterBuffer

, is a comma, so put all the contents of letterbuffer together as a Variable a => result, then push , as a Function Arg Separator => result

read 7=> numberBuffer

) is a Right Parenthesis, so put all the contents of numberbuffer together as a Literal 7 => result

Complete. You get the hang of it now, right?

We’re getting there, just a few more cases to handle.

This is the point where you sit down and think deeply about your algorithm and data modeling. What happens if my current character is an operator, and the numberBuffer is non-empty? Can both buffers ever simultaneously be non-empty?

Putting it all together, here’s what we come up with (the values to the left of the arrow depict our current character (ch) type, NB=numberbuffer, LB=letterbuffer, LP=left parenthesis, RP=right parenthesis

loop through the array:

what type is ch?

digit => push ch to NB

decimal point => push ch to NB

letter => join NB contents as one Literal and push to result, then push ch to LB

operator => join NB contents as one Literal and push to result OR push LB contents separately as Variables, then push ch to result

LP => join LB contents as one Function and push to result OR (join NB contents as one Literal and push to result, push Operator * to result), then push ch to result

RP => join NB contents as one Literal and push to result, push LB contents separately as Variables, then push ch to result

comma => join NB contents as one Literal and push to result, push LB contents separately as Variables, then push ch to result

end loop

join NB contents as one Literal and push to result, push LB contents separately as Variables,

Two things to note.

- Notice where I added “push Operator * to result”? That’s us converting the implicit multiplication to explicit. Also, when emptying the contents of LB separately as Variables, we need to remember to insert the multiplication Operator in between them.

- At the end of the function’s loop, we need to remember to empty whatever we have left in the buffers.

Translating It to Code

Putting it all together, your tokenize function should look like this now:

function Token(type, value) {

this.type = type;

this.value = value;

}

function isComma(ch) {

return /,/.test(ch);

}

function isDigit(ch) {

return /\d/.test(ch);

}

function isLetter(ch) {

return /[a-z]/i.test(ch);

}

function isOperator(ch) {

return /\+|-|\*|\/|\^/.test(ch);

}

function isLeftParenthesis(ch) {

return /\(/.test(ch);

}

function isRightParenthesis(ch) {

return /\)/.test(ch);

}

function tokenize(str) {

str.replace(/\s+/g, "");

str=str.split("");

var result=[];

var letterBuffer=[];

var numberBuffer=[];

str.forEach(function (char, idx) {

if(isDigit(char)) {

numberBuffer.push(char);

} else if(char==".") {

numberBuffer.push(char);

} else if (isLetter(char)) {

if(numberBuffer.length) {

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

result.push(new Token("Operator", "*"));

}

letterBuffer.push(char);

} else if (isOperator(char)) {

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

emptyLetterBufferAsVariables();

result.push(new Token("Operator", char));

} else if (isLeftParenthesis(char)) {

if(letterBuffer.length) {

result.push(new Token("Function", letterBuffer.join("")));

letterBuffer=[];

} else if(numberBuffer.length) {

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

result.push(new Token("Operator", "*"));

}

result.push(new Token("Left Parenthesis", char));

} else if (isRightParenthesis(char)) {

emptyLetterBufferAsVariables();

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

result.push(new Token("Right Parenthesis", char));

} else if (isComma(char)) {

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

emptyLetterBufferAsVariables();

result.push(new Token("Function Argument Separator", char));

}

});

if (numberBuffer.length) {

emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral();

}

if(letterBuffer.length) {

emptyLetterBufferAsVariables();

}

return result;

function emptyLetterBufferAsVariables() {

var l = letterBuffer.length;

for (var i = 0; i < l; i++) {

result.push(new Token("Variable", letterBuffer[i]));

if(i< l-1) { //there are more Variables left

result.push(new Token("Operator", "*"));

}

}

letterBuffer = [];

}

function emptyNumberBufferAsLiteral() {

if(numberBuffer.length) {

result.push(new Token("Literal", numberBuffer.join("")));

numberBuffer=[];

}

}

}

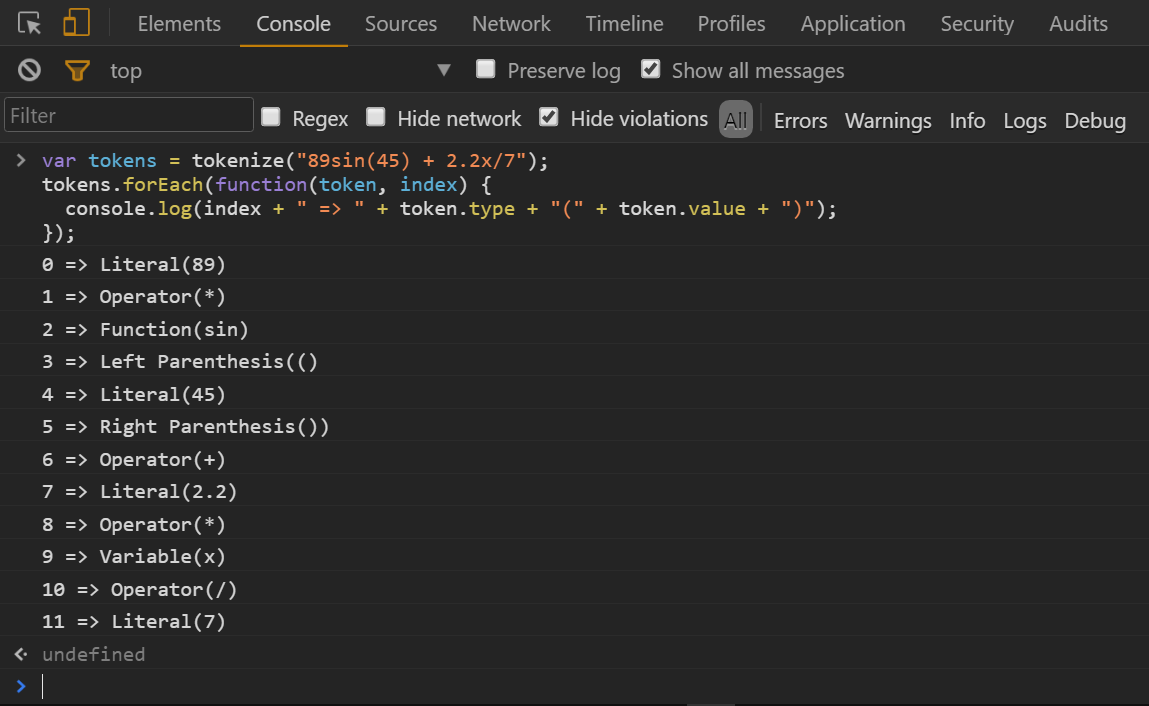

We can run a little demo:

var tokens = tokenize("89sin(45) + 2.2x/7");

tokens.forEach(function(token, index) {

console.log(index + "=> " + token.type + "(" + token.value + ")":

});

Yeah! Note the added *s for the implicit multiplications

Yeah! Note the added *s for the implicit multiplications

Wrapping It Up

This is the point where you analyze your function and measure what it does versus what you want it to do. Ask yourself questions like, “Does the function work as intended?” and “Have I covered all edge cases?”

Edge cases for this could include negative numbers and the like. You also run tests on the function. If at the end you are satisfied, you may then begin to seek out how you can improve it.

Thanks for reading. Please click the little heart to recommend this article, and share if you enjoyed it! And if you have tried another approach for building a math tokenizer, do let me know in the comments.

I write about my software engineering thoughts and experiments. Want to follow me? I don't have a newsletter; instead, I built Tentacle: tntcl.app/blog.shalvah.me.